Mozambique

September 2025

Once-thriving communities on the Afungi Peninsula of Palma Bay, in the far north of

Mozambique, have become landless, “slim”, and dispossessed of peaceful futures – as a

direct result of mega liquefied natural gas (LNG) projects majority owned by TotalEnergies,

ENI, and ExxonMobil.

The resettlement process for the communities required to relocate for the gas projects has

been mangled, and it is the most vulnerable who are paying the cost for energy giants to

industrialise their lands. While the Mozambique LNG project remains suspended, and two

others remain without final investment decision, African financial institutions must take the

moment to assess if they will continue their support for a project that has directly harmed

local peoples.

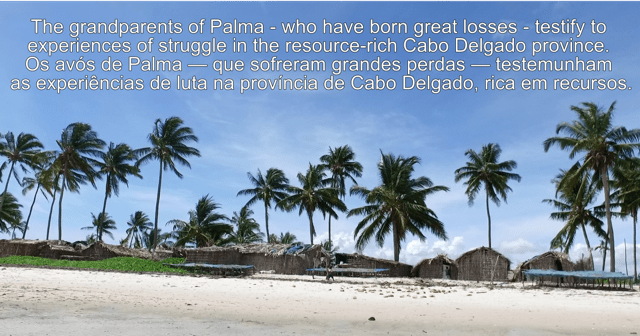

The grandparents of Palma – who have born great losses – testify to experiences of struggle

in the resource-rich Cabo Delgado province.

“Since the day we left until today, we have not received any support, not even farmland…at

my age, I can’t get food, I don’t have a farm,” explains Senhora. F, originally from

Barabarane village where she farmed, fished, and gathered firewood and medicines from the

land.

Senhora. A, who supported her family from the sale of fish brought in by local fishing boats

says: “Without fish I am lifeless…Our lives now are made up of land struggle.”

For the elderly of Palma, who have watched their communities disintegrate since the gas

companies arrived, there is now only a bleak hope that their families can live in dignity.

Commercially viable gas fields were found far offshore in the Rovuma Basin in around 2010.

Then, the grandparents of Palma were still strong, working the shore and their vast lands,

and spending long days at sea. Life was hard, and socio-economic conditions were not

idyllic, but they were surrounded by beauty, they had stable homes in thriving communities,

and their children were healthy.

When their lands were required for the gas projects, they entered into negotiations for

resettlement with hopes fed by promises of a better life for their children – promises of new

homes and farmlands to replace what they had lost, education and jobs for their children, a

hospital, a football field, and an expansion area for their children, who would soon start their

own families.The first families were relocated in 2019. Since then, they have been caught up

in negotiation processes aimed at serving the gas interests. The land and livelihoods they

hoped to leave as inheritance have become sites of struggle where their children – now

adults – are driven to protest at the company gates to demand what was promised to their

parents.

Senhor S, who lived his life and raised his children in Barabarane states, “My children left

behind land, houses, and everything they had, and to this day they have not been

compensated for their property.” He wears a kofi (a type of cloth cap) as a symbol of faith,

wisdom, and respect in the community.

Some lament their lost homes and destroyed livelihoods, and speak of poor or no

compensation, and no support. Many speak of hunger, of their children and neighbours

looking “slim”, of the daily search for food and water. In addition to lands taken, access is

now restricted to many important coastal and fishing grounds.

Senhor B, who once had a fishing business in Milamba village states, “With the arrival of the

company, I am unable to carry out fishing activities due to the resettlement they have

imposed on us…. I can’t feed my children either, as I did before Total came along.”

Losing land and access to the sea means losing the ability to survive. There are enormous

intangible losses that can never be compensated, such as the unforgettable flavor of local

food, guaranteed by the centuries-old mango trees; the shelter and food provided by the old

coconut palms; and the colorful bed mats woven from wild strawn.

Senhor S, who lost farmlands in Nsemo, explains that the limited cash compensation is not a

fair replacement for ever-providing natural resources, “If you give us money how are we

going to live as human beings? How will my children and grandchildren survive?”

French company TotalEnergies leads the resettlement work on the Afungi gas site, and is

majority owner of the Mozambique LNG project. The project shares land use rights for the

gas site with the Rovuma LNG project of Italian company ENI and American company

ExxonMobil. About 32 financial institutions have committed approximately USD 15 billion to

Mozambique LNG, including four South African banks and five African public institutions.

Collectively, the African financial institutions involved have committed around

USD 2.5 billion. All have been informed of the communities’ unresolved resettlement

grievances as well as other severe risks, including environmental and climate risks.

Over the years, tireless attempts and proposals from communities for a resolution were

largely ignored by the company, and formal complaints processes through the Mozambican

government yielded further delays. Confusion and tension were also created when fields in

some communities were taken – some without payment, some without even agreement –

and then allocated as compensation fields to resettled communities. A key flaw in the

resettlement process is that communities were not provided legal assistance, and civil

society organisations were impeded from providing support. It was only after a series of

brave protests starting in November 2024 that the gas company re-entered negotiation.

Since then, new agreements have been signed in some communities but payments have not

been made, and in other communities, negotiations are still underway.

Across Africa, similar grievances have been raised against TotalEnergies relating to lands

taken, livelihoods destroyed, inadequate or lack of compensation, and unmet compensation

promises, in addition to the severe environmental and climate risks of the company’s

projects, and links to human rights violations. In late August, affected communities and civil

society connected their struggles across the continent to call TotalEnergies and its

supporters to account. As part of the Kick Total Out of Africa week of action, the Cabo

Delgado communities spoke at an intercontinental tribunal, alongside communities in

Uganda, South African and the DRC, demanding accountability and reparations for the

socio-economic, environmental and human rights violations associated with the company.

In Palma, the gas-related displacement cannot be separated from the instability created by

the raging regional insurgency, or the responding militarisation of the region that was

accompanied by further extortion and violence against civilians. Ultimately, gas development

would deliver low economic benefits for Mozambique, and only after about another decade.

The projects make use of tax avoidance mechanisms, the gas stakes of Mozambican state

company ENH are considered to be “virtually worthess”, and the gas is already potentially

stranded.

Although there is ongoing insistence that the TotalEnergies project will resume (albeit with

shifting target dates), the risks associated with gas development remain extremely high. For

the people of Palma, the hopes of a better life from gas have become a reality of loss and

hunger. Financial institutions must take into account the real experiences of the men and

women who have witnessed the projects unfolding and experienced their impacts. They

must withdraw their support for development that offers little to Mozambique in return for the

lands and sea it takes.