Please note: This letter is addressed to the Implementation Office of the Mphanda Nkuwa Dam Project, which according to local news, was created by Ministerial Decree in February 2019 and would be functioning under the Ministry of Mineral Resources and Energy (MIREME). However, we could not find any information about who or where to deliver this letter, not even in MIREME. Due to this, JA! delivered this letter only to MIREME and MITADER (Ministry of Land, Environment and Rural Development).

TO THE IMPLEMENTATION OFFICE OF THE MPHANDA NKUWA DAM PROJECT

cc: Ministry of Land, Environment and Rural Development

Ministry of Mineral Resources and Energy

Maputo, 14th of March 2019

JUSTIÇA AMBIENTAL (JA), a Mozambican civil society organization committed to the defense of environmental and land rights of local communities, hereby expresses its total repudiation for the Mozambican government’s persistence on seeking to make feasible and implement the controversial Mphanda Nkuwa hydroelectric project, proposed for the Zambezi River, in the Tete province. Here are some of our concerns about the project, highlighting some of its potential environmental, climatic, social and economic impacts.

Brief history of the Mphanda Nkuwa project

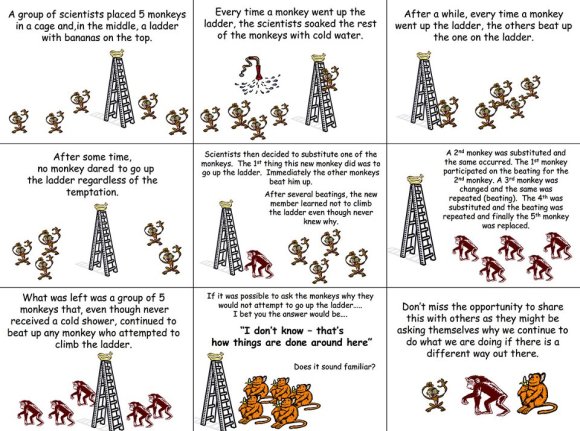

In the 90’s, the UTIP (Hydroelectric Projects Implementation Unit) was created with the mandate to implement the Mphanda Nkuwa project proposal. Thousands of dollars were spent on feasibility studies and on the environmental impact assessment, among several other studies, most of which of poor scientific quality. Years later and after thousands of dollars were spent, UTIP was extinct. However, this did not mean the Mozambican people were any closer to reaching a viable and sustainable energy solution.

In the 2000s, the Mphanda Nkuwa consortium was established, with EDM holding 20%, Insitec 40% and Camargo Corrêa 40%. At this stage, more studies were elaborated and thousands of dollars more were wasted. The Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) was approved in 2011, with huge and serious flaws, leaving many of the issues and concerns we rose at the time unanswered. This consortium was equally extinct before the project got to move forward.

In the past two years, this project started being mentioned as a government priority again. Hence, in February 2019, the Implementation Office of the Mphanda Nkwua Dam Project was created by Ministerial Diploma. In March, an international open tender was launched for the selection of the consulting firm that will assist the Executive in designing the legal and financial structuring strategy of the Mphanda Nkuwa Dam Project. The consultancy includes the energy transport system and associated infrastructures. Everything indicates that we are going to witness, yet another waste of thousands of dollars in endless consultancies and studies that will, most likely, remain in the secret of the gods.

What we would like to know from our government is how much money has been invested in this project so far – since the UTIP, through the controversial and incomplete EIA, up to the present day? What are the concrete results of the thousands of dollars that have been invested over the past 19 years?

Regarding the environmental, climatic, social and economic impacts of mega-dams, in particular on the Zambezi River

The project establishes that the Mphanda Nkuwa Dam will be built just 70km downstream from the Cahora Bassa Dam, which could aggravate the already serious negative impacts of existing dams along the Zambezi River.

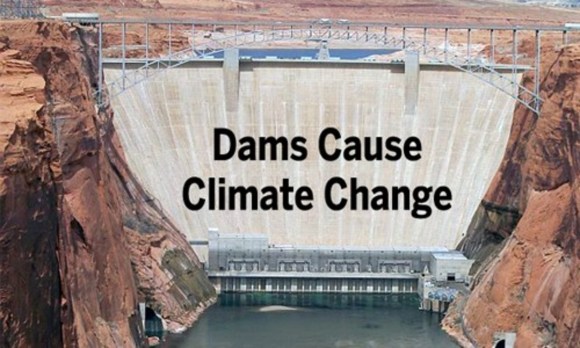

This project will have very serious social and environmental impacts (in particular for local communities), and there is no chance it will bring the country the economic benefits claimed by its proponents. The EIA approved in 2011 did not contemplate the risk of induced seismicity, it did not contemplate the impact of climate change on river flow (and the consequent reduction in estimated energy production), nor did it contemplate the financial risk that the project represents. Why does our government continue to ignore all these facts and flaws?

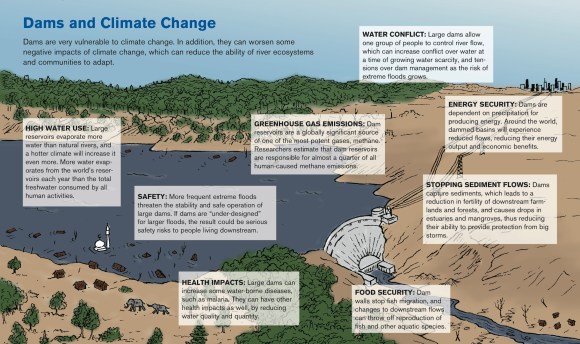

The Zambezi River is the 4th largest river in Africa and an estimated 32 million people live on its banks, 80% of whom depend directly on the river for subsistence through agriculture and fishing. In the specific case of the Mphanda Nkuwa project, the environmental unfeasibility of which we speak is not only justified by the fundamental perspective of ecological preservation, since it also translates into a blatant and unquestionable economic unfeasibility. Taking into account the reports of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change and International Rivers, even without the dam in Mphanda Nkuwa, the Zambezi is already one of the rivers in Africa that will most suffer the impacts of climate change (partially because of the greenhouse gas emissions caused by mega-dams) due to intense droughts and floods that are projected to the continent in the medium and long term. Such climatic events will certainly jeopardize the energy production of its various dams – especially Mozambique’s dams, which stand at the end of the line. Specifically regarding the flow of the Zambezi River, studies predict that by 2050 there will be a considerable reduction of 26-40% of its flow. This data is not being considered, nor is it even being debated. Will we have to wait until 2050 to see this scenario materialize along with all the negative impacts on the local communities and on the rich ecosystem of the Zambezi Delta to believe in it?

Countless studies and concrete examples demonstrate that it is a mistake to continue to insist on the construction of large and mega-dams for energy production. An Oxford study looked at all the dams built between 1934 and 2007 and concluded that large and mega-dams end up 96% more expensive than the initial project, and take 44% longer than estimated to get built. There is also sufficient evidence that there is an urgent need to make an energy transition and diversification, by abandoning traditional and obsolete sources of energy and adopting clean and renewable energy sources. There are currently countless countries that have distanced themselves from this type of solutions, in the last 100 years, in the US alone, about 1150 dams have been demolished!

The recent floods on the Revuboé River, which are affecting the centre of the country and all the communities living along the banks of the this river and of the Zambezi River, are yet another prove that dams (especially those of this size) are not suitable to mitigate the impacts of floods and droughts. On the contrary, large and mega-dams exacerbate these impacts, since their main (and, in most cases, only) purpose is the generation of hydropower. To reach their maximum production capacity, the reservoirs must accumulate as much water as possible. In case of floods, the dam is forced to release the stored water, causing even more destruction in the existing communities and infrastructures along the river bank.

Without a doubt, energy is a fundamental and indispensable asset for the development of a nation, however, there is enough scientific evidence that large dams do not bring the desired benefits, specially for those who need them the most. The truth is that the energy produced in mega-dams does not benefit the local populations and serves mostly for export and supply of energy-intensive industries, as the Cahora Bassa Dam exemplifies. The successive and unannounced high increases in the price of energy that Mozambicans have faced over the past five years, clearly show that our government has not been able to properly manage the energy it already produces, nor has it been able to plan properly and seek solutions that take into consideration the present shameful and sad situation of crisis in which the country is immersed.

In conclusion:

Given the information presented above, and in numerous studies and scientific analysis that we can make available if you are interested, we must ask you: Why are we rowing against the tide? We demand the government explain to us clearly and comprehensively the contours, objectives and the rational behind this project, including:

• Where does the investment come from and in exchange for what?

• Why is this project a priority for the country (taking into account the current socio-economic situation)?

• Have other alternatives been considered? If so, which ones?

• Who will be responsible for compensating the communities that, for over 19 years, have had their future on hold, unable to invest in their community and to build any infrastructure, for fear of losing their investments? These communities heard about the Mphanda Nkuwa dam project for the first time in 2000 and were warned not to build new infrastructures because they would not be compensated at the time of resettlement. To date they have received no other information from the government.

• What is the real purpose of the dam and what hypothetical benefits do you think it would bring the country in the short, medium and long term, including how do you plan to monetize it? Considering that Eskom (our main customer) is the electricity company that buys energy at the lowest price in the world, from us… and also remembering that, at present, Mozambicans are paying one of the highest rates of energy consumption in Africa, behind only 3 countries.

If the Government’s priority is really development, there are a number of other energy options that need to be duly studied and widely debated, such as clean renewable energy sources, so that the decision that needs to be made is the most correct and fair socially, environmentally and economically. Once again, Justiça Ambiental is available to help find alternatives that are in line with a truly inclusive and sustainable development, suitable for the majority of Mozambicans. Or do we have to make the same mistakes again? Or do you wish to tell us then that you did not see it coming?

Photograph taken in Maputo, in an action to raise awareness about the impacts of the proposed Mphanda Nkuwa dam, on March 14th 2019, International Day of Action for Rivers.