14 June 2019

Rome

I represent an organisation called Justica Ambiental/Friends of the Earth Mozambique in maputo. I’ve come quite a long way to ask Eni some questions… I will ask in particular questions about the onshore and offshore work in Area 1 and Area 4 of the Rovuma Basin in Mozambique, which includes the Coral Floating Liquid Natural Gas Project, and the Mozambique Liquid Natural Gas Project, and the offshore oil and gas exploration in Block ER236 off the South Coast of Durban in South Africa.

we want to give some context to the shareholders:

Although the extraction in Mozambique has not yet begun, already the project has taken land from thousands of local communities and forcefully removed them from their homes. We work with and visit most regularly the villages of Milamba. Senga and Quitupo. The project has taken away people’s agricultural land, and has instead provided them with compensatory land which is far from their homes and in many cases, inarable. Fishing communities which live within 100 metres of the sea are now being moved 10 km inland.

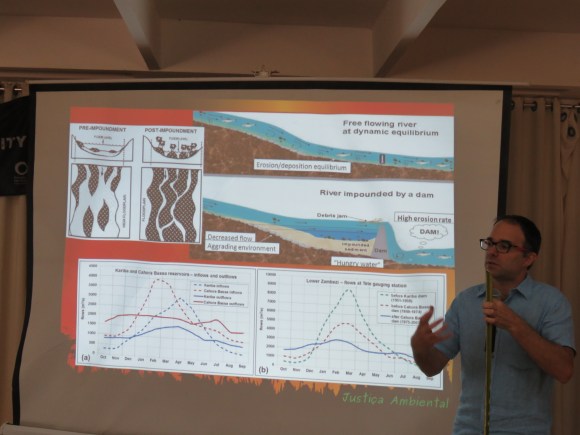

Furthermore, the noise from the drilling will chase fish away from the regular fishing area, and the drilling and dredging will raise mud from the seabed which will make fishing even more difficult with little visibility.

There is little to no information about the type of compensation people will receive. Communities think the ways in which people’s compensation has been measured and assessed is ridiculous. For example, the company assesses someone’s land by counting their belongings and compensating them financially for those goods. Another way is by counting the number of palm trees that one person has on their land. Most people have been given a standard size of land of 1 hectare. This is regardless of whether they currently have 1 hectare, 5 hectares, or even ten hectares.

80% of Mozambicans don’t have access to electricity, and need energy to live dignified lives. Despite this incredibly low electricity rate, the LNG projects will not help Mozambique and its people benefit from its resources. Instead the LNG will be processes and exported to other countries, in particular Asia and Europe.

The projects will have a huge negative impact on the local environment, destroying areas of pristine coral reefs, mangroves, and seagrass beds, including endangered flora and fauna in the Quirimbas Archipelago, a UNESCO Biosphere.

Mozambique is a country that is already facing the impacts of climate change. In the last two months, two cyclones hit the country hard, as we saw most recent with Cyclone Idai and Cyclone Kenneth that together killed over 600 people and affected at least 2 million.. The EIA admits that the contribution of the project’s greenhouse gases to Mozambique’s carbon emissions will be major.

This project will require a huge investment by the Mozambican government, which would be better spent on social programs and renewable energy development. The project itself will require an investment of up US$ 30 billion. This project will divert funds that should be going to education and other social necessities, including $2 billion that the World Bank estimates is necessary to rebuild the country after the cyclones, in order to build and maintain infrastructure needed for the gas projects.

Over the last year and a half, there as been a scourge of attacks on communities in the gas region, which many communities believe are linked to the gas projects because they only began once gas companies became visible. In order to ensure the security of the gas companies and contractors, the military has been deployed in the area and maintains a strong presence, and several foreign private security companies have been contracted by the companies.

SOUTH AFRICA

While the human rights and environmental violations against the people of the South Coast are many, the particular issue I’d like to raise is that of the lack of meaningful public participation with the affected communities, who were totally excluded from the process.

Exclusivity of meetings:

Eni held a total of 5 meetings.

Three of them were at upper end hotels and country clubs in the middle class areas of Richards Bay, Port Shepstone and in Durban. This is extremely unrepresentative of the vast majority of people who will be affected, many of whom live in dire poverty: communities of as Kosi Bay, Sodwana Bay, St Lucia,, Hluluwe, Mtubatuba, Mtunzini, Stanger, Tongaat, La Mercy, Umdloti, Verulam, Umhlanga, Central Durban, Bluff, Merebank, Isipingo, Amanzimtoti, Illovu, Umkomaas, Ifafa Beach, Scottsburgh, Margate, Mtwalume, Port Edward and surrounding townships like Chatsworth, Inanda, Umlazi, Phoenix and KwaMakhuta. This is blatant social exclusion and discrimination.

During the two so-called public participation meetings with poorer communities in February and October 2018, attended by both Eni and consultants Environmental Resources Management, the majority of people affected were not invited. The meetings, held by Allesandro Gelmetti and Fabrizio Fecoraro were held in a tiny room with no chairs. Eni had not invited any government officials.

[Sasol head of group medial liaison Alex Anderson, confirming the meeting, said: “Eni, our partner, is the operator and the entity managing this process. Sasol is committed to open and transparent engagement with all stakeholders on this project, as it’s an ongoing process over the coming year. We value the engagement and the feedback we receive, so that we consider stakeholder concerns into the development of the project.”]

Eni says it dropped the finalised EIA’s off at 5 libraries for the interested parties to read. However these libraries are difficult for most of the affected communities to travel to, and one of the libraries, Port Shepstone library, was in fact closed for renovations at the time.

QUESTIONS:

Civil society in Mozambique:

The response to our question was not answered, and I would like to reformulate it.

Is Eni working with any Mozambican organisations as part of its community engagement, and which are they?

Is Eni working with any organisations, Mozambican and from elsewhere, who are NOT paid by the company?

Reforestation:

I’d like to quote an article in the FT article David Sheppard and Leslie Cook 15 March 2019- Eni to plant vast forest in push to cut greenhouse gas emissions, which says, I quote:

“by planting trees which absorb CO2 from the atmosphere, companies like Eni are looking to offset their pollution that their traditional operations create.”

“Italian energy giant Eni will plant a forest 4 times the size of Wales as part of plans to cut greenhouse gas emissions”

1. Does Eni dispute the truthfulness of the Financial Times article

Eni says that it has already begun the contract process with the governments of the countries in Southern Africa, where these forest projects will take place.

1. Has the company assessed whether there actually is 81 000 hectares of unused land available for this project?

2. Has Eni already held any public participation meetings with the communities who live on the land that will be used for ?

3. who is doing this assessment and when will it begin

4. how many communities and people will be affected?

EIA ‘s:

1. In the case of Area 1, Eni responded that the responsibility for ongoing public participation with the communities of Cabo Delgado lies with Anadarko for the joint EIA. Does Eni confirm it is relying on another company to guarantee that its own project fulfills requirements for an EIA?

2. Also on Area 1, the last EIA was done in 2014? Why does Eni rely on an impact assessment that is 5 years old?

3. Eni has responded that it only concluded its EIA in 2014, but had already begun seismic studies in 2007 and prepared for exploration in 2010. Furthermore, Eni only received its license from the Mozambique government in 2015. This is a whole 8 years after it had begun seismic studies.

Why did Eni begin studies that affect the environment and people before completing an EIA?

Decarbonisation:

This question was not sufficiently answered: I have asked why Eni’s decarbonisation strategy does not align with its actions in Mozambique, where the EIA says, and I quote from Chapter 12: “The project is expected to emit approximately 13 million tonnes of CO2 during full operation of 6 LNG trains.”

By 2022 “the project will increase the level of Mozambique’s GHG emissions by 9.4%”

“The duration of the impact is regarded as permanent, as science has indicated that the persistence of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is said to range between 100 and 500 years, and therefore continues beyond the life of the project”.

I ask again, how does this align with Eni’s decarbonisation strategy?

Private security:

1. Who is Eni using as their private security companies in Mozambique and in South Africa?

2. What was the legal process the company went through to contract these private security companies?

3. If any companies are not registered locally, what legal process did Eni go through to bring them to Mozambique and South Africa?

Contractors:

1. Will Eni provide us with a list of all their contractors in Mozambique and in South Africa?

2. if not why not?

Jobs in South Africa:

You have not answered our question here –

How many jobs will Eni create at its operation in SA?

How many of these jobs will be paid by Eni?

Contract

I ask this in the name of the South Durban Community Environmental Alliance. The organisation requested Eni to make available the contract signed with the Dept of Environmental Affairs and Petroleum Agency South Africa that gives Eni permission to conduct seismic testing. Eni has said no, because the right to the document lies with a contractor.

When JA! team visited Pemba at the end of February, 2019, the biggest city in Cabo Delgado province, to learn about the current situation of the ‘gas rush’ in northern Mozambique, it quickly became apparent to us that there is very little clarity and transparency about what is actually happening in the gas industry. Attacks on communities, land grabs, the stage of the companies’ operations, and even which companies are involved, have left people uncertain and confused.

When JA! team visited Pemba at the end of February, 2019, the biggest city in Cabo Delgado province, to learn about the current situation of the ‘gas rush’ in northern Mozambique, it quickly became apparent to us that there is very little clarity and transparency about what is actually happening in the gas industry. Attacks on communities, land grabs, the stage of the companies’ operations, and even which companies are involved, have left people uncertain and confused.